Black/Venice, Italy/October 2019

This podcast brings us to Venice, Italy, to talk about the color black. We find black in the iconic gondola, in the paintings of Tintoretto, the son of a fabric dyer. We find it in imported spices like coffee and pepper, and local resources like sepia, an artists’ pigment and a foodstuff. There is black in the industries of trade, shipbuilding, printing, and glass manufacture, in ideas of race and fashion, in the politics of secrecy and the poetics of night.

About Black

All colors hold symbolism, but black seems to be one with a long history of meaning that has expanded and changed the most over time. It has been a signal of piety, simple elegance, romance, and anarchy. It has naturally been aligned with darkness and mystery and therefore death and evil. Many images of Satan in medieval paintings are depicted as a black devil devouring sinners. It is associated with the act of mourning in Western culture, but has grown into a symbol of high fashion.

The idea of black as a color can be debated. Some artists prefer to create a chromatic black that is made by mixing pure colors from the spectrum, while others prefer to use a black in its purest form -- one that is an abyss, the night sky, and without light.

There are several types of black dyes and pigments, and different ways of attaining them. Many simple black colors are carbonized matter, such as bone or grape vines, and simply soot, the residue of a burning flame of animal fat, oil, or wax. All of these have been known at least since antiquity. Iron gall ink, made from common oak galls, was the principal writing ink until the 19th century.

Our main reason for pairing Venice with black is the Seppia, or cuttlefish. It is a great example of a resource being used both as a food and as a pigment, and is an important part of Venetian cuisine due to its availability in the Adriatic Sea and the Venice lagoon. Cuttlefish ink is both a durable pigment and a culinary delicacy. Harvested from a gland inside the cuttlefish, it is a warm black color and a dense consistency like paste. Its purpose in nature is of course to create a dark cloud in the water to escape from predators. As an ink, it is consistent, fine, and makes an excellent colorant.

Sepia pigment was traded through Venice. The sacks of ink were collected, dried, and sold directly to artists or colorists. It is then ground and re-hydrated with a medium, usually water, for drawing and writing. Today, cuttlefish ink can be purchased in different formats and consistencies as a food stuff. It is readily and cheaply available in ketchup-sized packets at Italian groceries. Cuttlefish and cuttlefish ink are the protagonists of a classic Venetian dish, Risotto al Nero, or risotto di seppia. The dish originated in the Adriatic, possibly in Croatia, and has become a symbol of Venetian cuisine. Here the cuttlefish itself is diced and sautéed, and after the rice has been added, the ink is incorporated with the broth.

About Venice

Once we settled on Venice as our location for black, we very quickly found many other connections besides seppia. Perhaps foremost, the poetry of darkness pervades the ambience of Venice. Even though everyone equates it with the brilliant light and reflections of the sky off the water and white buildings, the shadows are what also enticed us. The same sea that reflects the sky, is deep and dark and Venice is notorious as a city for getting lost, especially at night. Like the inky cloak of the seppia, the mysteries of Venice are hidden in plain sight around each corner.

One of the most famous symbols of Venice, the gondola, originates from around 1000AD. It is meticulously treated with layers of black lacquer, much like the luminous glazing by the city’s best picture painters. Gondola lacquer is made with pine soot and resin or boiled linseed oil, and tar or pitch. Its color relates strongly to materials used, but it is also a result of a legal mandate. The gondola, a luxury craft, was often painted bright, garish colors, with gold inlays, as a way of advertising wealth. As early as 1609 the Venetians issued decrees to ensure that all gondolas were equal, and only black. Some say the black may be the color of elegance, or the color of mourning for the victims of the plague.

Circa 1500, Venice was one of the most important centers for fabric dyeing. Until the 14th century, black dyes were made from tree bark, and were rather grey or brown. Using oak galls, dyers were able to get a richer, long lasting black. With Venice being the epicenter for global trade, not only lush silks from the East, but also brazilwood and indigo from India were imported. In 1429 the Venetian Dyers Guild published recipes for dyes and The Plictho dell'arti de Tentori by Venetian author Giovanni Ventur Rosetti was published in the 1540’s. These books listed instructions for using indigo, and some 200 other recipes for dyeing cloth, linen, cotton and silk with many varieties of dyestuffs.

The availability of books of knowledge was due to Venice being a publishing capital of Europe and its openness to commerce, free trade, and immigration. We cannot ignore the obvious material of ink which was oil-based and included soot and pitch used for printing. With the importation of the printing press from German immigrants, perhaps the biggest revolution was the invention of small portable books, like the modern day paperback. Aldo Munzio’s “movable print” led to the “movable book,” and made publications affordable. This climate of material and intellectual commerce, in addition to freedom from Papal censors, allowed printing to thrive in Venice. Along with the this printing boom in Venice, we see the first Books of Secrets. These books were collections of medicinal remedies, cosmetics, cures and perfumes, and recipes for artists’ materials and pigments. They were guarded recipes, gathered from all over, from doctors, artists, and housewives. Many of the recipes share ingredients that intersect across multiple commercial sectors—art, cooking, medicine, and the common household.

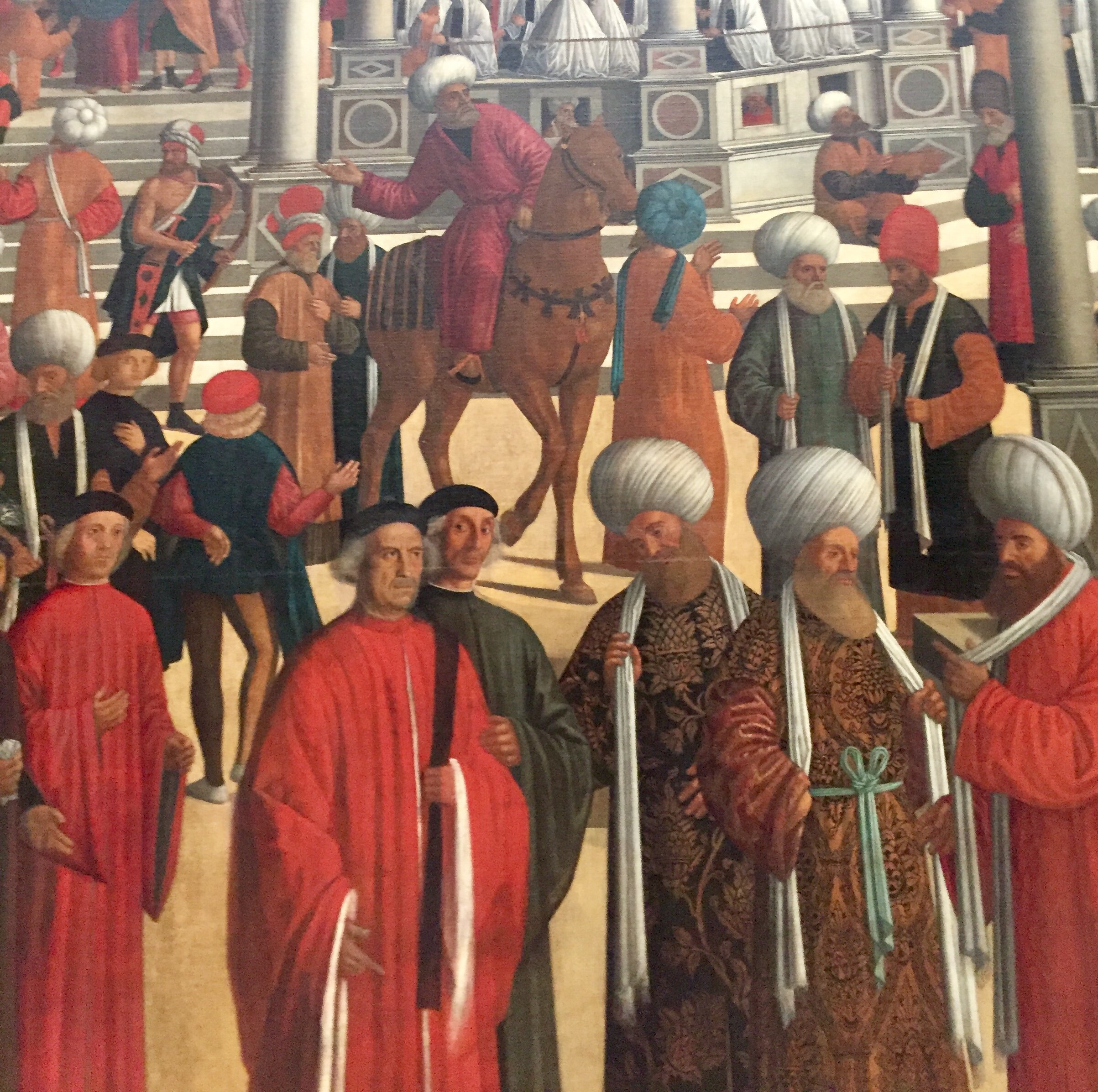

We also would be remiss if we did not touch upon the issue of race while discussing blackness. Many streets are named Schiavi Mori (Moorish Slaves). The word “Moor” means black, but can refer to Africans, Arabs, and slaves. Venice, circa 1500 was perhaps the most cosmopolitan city in the world, where people of diverse races and religions worked and lived together. However, the institutionalized racism in connection to its vast wealth and trade is evident in paintings where African slaves are portrayed as servants and gondoliers. In a painting by Vittore Carpaccio, "Miracolo della reliquia della croce a ponte di Rialto" (1494), there is an African gondolier prominently featured. We don’t know much about him other than he is dressed finely and has a beautiful dagger. This obvious presence in the foreground can be read as a status symbol, showing the city’s blatant power of possession. Until the discovery of “The New World,” slavery was much more democratic- anyone could be a slave if defeated. With the advent of the African diaspora, slavery became synonymous with blackness. The monument for Doge Pesaro (1669) at the Church of the Frari is a glaring example of this shift. Giant muscular black men sculpted out of black marble with glowing white eyes and bowed heads struggle to hold up the entire tomb and the Western world.

This explicit show of power reflects the abundance of wealth from international trade that Venice had become known for. As the culminal stop of the Spice Trade Route, Venice was the most important trade center by this time. An international hub, the spice trade was particularly lucrative, where the availability of pepper and cinnamon from India, ginger from China, and nutmeg from Malaysia, quickly became status symbols among the wealthy. These were used in cooking, but also in the growing discipline of medicine. Coffee, which came to Europe by Venetian trade, brought the initial coffee shop culture to Europe. In addition to one of the most important fabric dyeing and book printing centers in the world, Venice was also Europe’s biggest and most important glass making industry, located on the island of Murano since 1291.

The influence of the import of textiles/canvas and fabric dyeing industry on the painter Tintoretto, whose father was a dyer, was strongly influenced by the import of canvas for the Arsenale which was the largest and most productive shipyard in the world circa 1500. The poet Dante was so impressed by the Arsenale’s command that the 21st canto of the Inferno refers to the consequence of swindlers to be immersed in boiling black pitch

Quale nell'Arzanà de' Vinizianibolle l'inverno la tenace pecea rimpalmare i legni lor non sani […]

The abundance of canvas for making sails influenced a new painting support for artists, and industry by-products like tar, or bitumen, infiltrated the Venetian painter’s palette. Tintoretto’s enormous oil paintings on canvas, made to fit the architecture of a space, are a testament to these new developments. Venice, by the first half of the 16th century possessed all the attributes to be a color center, and where we find the first “vendicolori,” or pigment sellers, with pigments like lapis lazuli coming from Afghanistan. Interestingly, the Arsenale, although no longer open for shipbuilding, continues to be a conduit for global influence. Today it is the location for the world famous Venice Biennale where 600,000 cultural tourists from all over come to see the most famous international artists showcase their art.

International trade adversely brought with it The Black Death, most likely carried along the Silk Road with fleas and rats on merchant ships traveling to Venice. A series of plagues occurred from the 1300’s through 1680 and decimated the population and in turn led to Venice’s economic decline and the eventual conquest by Napoleon. Today, Carnivale celebrates and remembers this past with costumes from the time, in particular the famous Doctor dressed in black and wearing a mask resembling a crow.

Since its early beginnings as a place of refuge for those fleeing barbarian conquerors, Venice continues to be a place of escape and self-imposed creative exile. Artists such as John Singer Sargent, John Ruskin, and the arts patron Peggy Guggenheim all repeatedly visited or found their home away from home in Venice. The poet Ezra Pound found solace and inspiration, visiting as a young man and living his final years in Venice. His dark past affiliated with the Fascist Party and their adopting of the color black cannot be denied. He is buried on the nearby cemetery island San Michele, however, his poetry lives on.

well, my window

looked out on the Squero where Ogni Santi

meets San Trovaso

things have ends and beginnings

(from Pound’s Canto LXXVI)

What brought us to Venice is what remains—the poetics of place and color and how they are intertwined. Black as a pigment, made primarily from burning organic matter, is arguably the oldest and most common color we know. But it also represents the darkness, the night, and secrecy. It represents the exotic and unknown, both fear and respect, something both eternal and impending. The most important merchandise to move in and out of Venice was culture itself. This sharing of goods, customs, and finally ideas, has created a visual and material legacy and a model of contemporary society.